This article was first published in the April 2015 edition of Recorder News, the magazine of BRISC - Biological Recording in Scotland (www.brisc.org.uk)

As a bat specialist I am regularly asked why bats are protected

when they seem to be quite common. To the uninitiated a bat is just a bat, but

we have at least ten species in Scotland and whilst some are relatively common

several are much rarer.

Bat populations today are a fraction of what they were

a few decades ago and, whilst the decline of some species appears to have

slowed, recovery to previous population levels is a long way off. Even the

Soprano Pipistrelle (Pipistrellus

pygmaeus)and Common Pipistrelle (P.

pipistrellus), our two commonest Scottish bat species and most often seen

due to its habit of emerging before full darkness, face a plethora of threats.

What often isn’t recognised is the vulnerability of bats in

our temperate climate. The females of most Scottish bat species are only

capable of giving birth to one juvenile per year (Noctules are an exception,

occasionally having twins). From the moment of birth the clock is ticking and

time is against each tiny and utterly dependent baby bat. They have to grow at

a prodigious rate from birth in June to be ready to fly around two months

later. They then have to rapidly climb a massive learning: in around three

months not only do they have to learn to fly with sufficient skill and agility

to outwit and capture their insect prey but they need to do so with sufficient proficiency

to rapidly build fat reserves in readiness for hibernation. Insufficient fat will result in a failure to

survive hibernation.

It’s no easier for the adults. Females spent the summer

devoting all their energy to hunting and feeding their young and now they too

have a limited time to build fat reserves. Males have an easier summer but must

work hard through autumn, attracting females to mate before they hibernate too.

Scottish bats live on a knife-edge at the best of times, so the

negative effects of human activity are especially pronounced. Agricultural

pesticides and development have reduced hunting habitat and prey availability.

Timber treatment of older buildings has been harmful to attic-roosting bats

(though the worst chemicals are now banned). Conversion of old agricultural and

industrial buildings has removed many roosting opportunities and though legislation

protects roosts in buildings from disturbance or destruction, implementation of

the law varies from local authority to local authority. Fragmentation of

habitat is especially problematic for bats: a single bat colony may use dozens

of roosts for different purposes through the year and they need safe commuting

routes to link these with each other and with suitable foraging habitat.

Removal of hedgerows and tree-lines reduces their ability to commute freely

between these locations. Sadly, deliberate destruction of bat roosts by

indifferent or ill-informed people is far from unknown.

A hibernating Brown Long-eared Bat (Plecotus auritus)

During hibernation bats enter a condition of deep torpor,

reducing their body temperature to between 2 and 8 degrees Celsius, slowing

their heart rate to as little at 10 beats per hour and breathing perhaps once

per hour. This reduces their use of stored energy to the minimum that supports

life. But hibernation is not continuous and bats regularly wake, sometimes

moving location. They may even hunt if the weather is warmer and Pipistrelles

are occasionally seen in daytime, hunting for winter-flying insects in the

midday sun. However arousal from deep torpor is expensive in energy and being

forced to arouse by disturbance can reduce a bat’s ability to survive

hibernation.

Conditions within hibernacula are critically important.

Temperature must be steady, usually between 2 and 8 degrees Celsius. High

humidity minimises water loss, reducing the need for bats to arouse to drink.

It can take up to half an hour for a bat to arouse from deep torpor, so safety

from predators is important, as is a lack of human disturbance. Hibernation

tales place in differing locations, depending on the bat species. Noctules (Nyctalus noctula) and Leisler’s Bats (N. leisleri) tend to hibernate in deep

tree holes, Pipistrelles (Pipistrellus

sp.) often use crevices in buildings, cliffs or under loose tree bark

which, whilst appearing relatively exposed, contain a suitable microclimate.

Underground hibernacula such as caves, mines and tunnels tend to be used by

bats of the Myotis genus - Daubenton’s

(M. daubentonii), Natterer’s (M. nattereri), Whiskered (M. mystacinus) and Brandt’s (M. brandtii) - and Brown Long-eared Bats

(Plecotus auritus).

Man-made or natural underground sites with suitable

conditions for hibernation are uncommon and increasingly under threat. In the

Lothians disused limestone mines are well-used and are usually located at the

base of quarries. Out of six mines known to be used by hibernating bats one is

regularly disturbed by members of the public, one is unsafe due to vibration from

an adjacent land-fill site and the landowner at another site recently had to be

warned by SEPA to cease illegal landfill activity.

The quarry at Hope Mine, near Pathhead was filled in during

the 1990’s and 2000’s. Access for bats was maintained via a grilled access hole.

Airflow is critical in underground hibernacula: warm, stale air needs to be

continually vented to maintain suitable hibernation conditions. At Hope a

subsequent underground rock-fall and lack of maintenance of the air vent

installed in the 1980s has caused the temperature underground to reach levels

of over 14 degrees, rendering the mine unusable by hibernating bats.

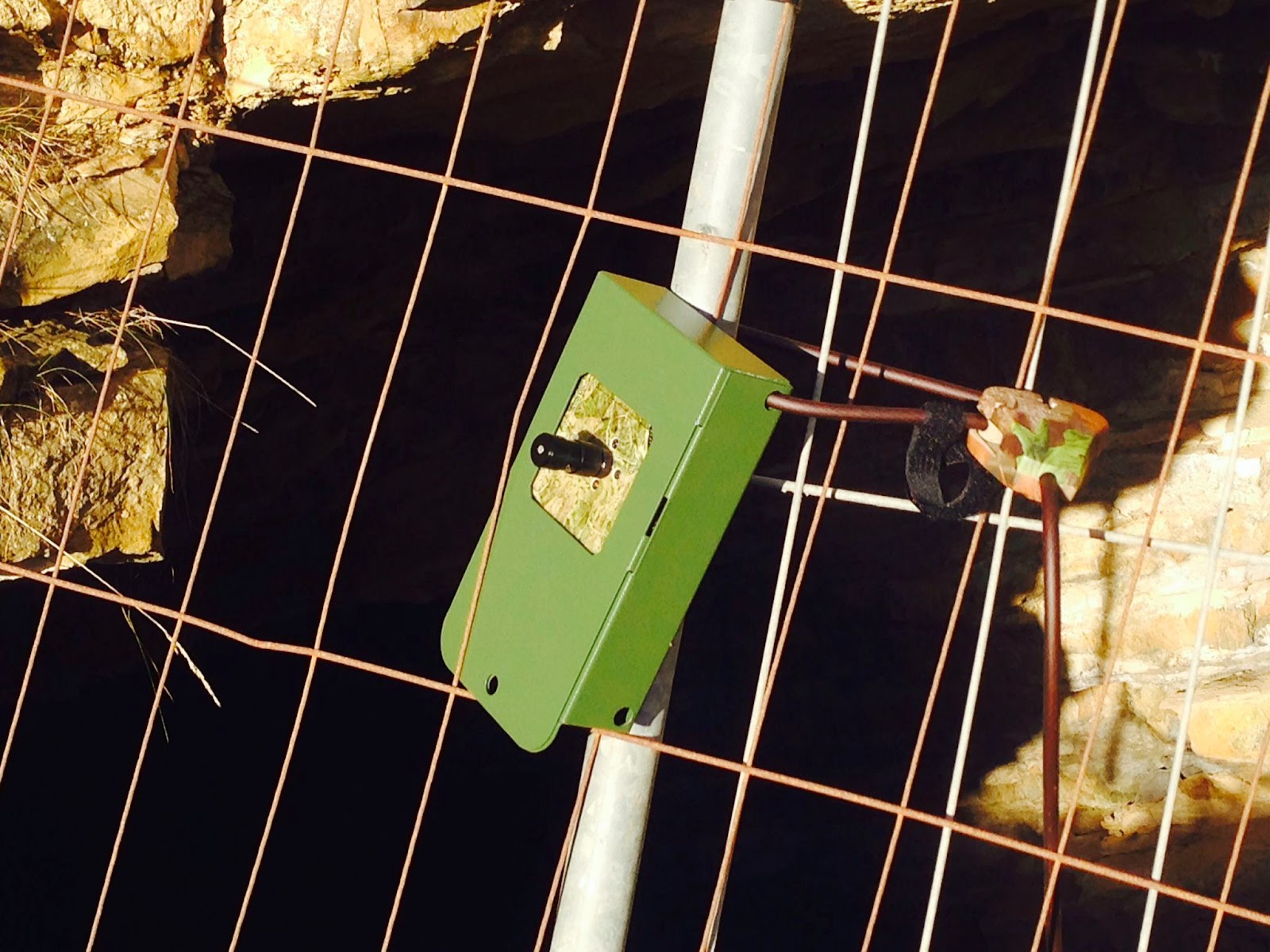

There is a happier story at the remaining two mines. Middleton

Upper Quarry near Gorebridge has recently been filled with over 600,000 tonnes

of spoil from the Borders Railway. My company (David Dodds Associates Ltd.) worked

closely with NWH Group, the owners and operators of the site. We used acoustic

monitoring to assess which access tunnels were favoured by bats entering and

leaving the disused mine workings. Under a Scottish Natural Heritage derogation

license NWH staff used gabion baskets to create a safe access route for bats to

continue accessing the mine after the quarry was filled in. Although the

appearance of the site has changed considerably, a section of cliff face above

the favoured entrance has been retained and stabilised, acting as a sign-post

towards the entrance favoured by the bats. The position of this entrance within the mine

allows warm air to vent naturally, but an additional ventilation pipe has also

been installed to ensure that temperature conditions remain suitable should

that change. I’m happy to say that the first underground survey, during January

2015 showed that the mine continues to be used by Natterer’s, Daubenton’s and

Brown Long-eared Bats. We hope to use a

similar approach to the adjacent Middleton Lower Quarry in due course.

Middleton Upper Quarry - an underground hibernaculum successfully safeguarded

(photo courtesy of Birch Tree Images www.birchtreeimagesphotography.co.uk)

The National Bat Monitoring Programme (NBMP) is managed by

the Bat Conservation Trust (BCT) on behalf of a partnership including BCT and

the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC). This programme is an excellent

example of citizen science at its very best. Throughout each year volunteers

all over the UK carry out a variety of different bat surveys, from walked

transects in open country or along watercourses, to counts of bats emerging at

known roosts and searches for bats swarming at roosts at dawn.

The slow and difficult search for hibernating bats

(photo courtesy of Birch Tree Images www.birchtreeimagesphotography.co.uk)

The surveys are

designed to allow anyone to make a contribution, from those with virtually no

experience of bats to skilled, licensed bat-workers. The NBMP website includes

training materials and bat detector training courses are regularly run, to

ensure as many people as possible take part. The NBMP data is collated and used

to provide a statistically robust assessment of how bat populations are faring

in the UK and in Scotland where sufficient data is available (more volunteer

surveyors are urgently needed by the NBMP in Scotland), published each year as

“The State of the UK’s Bats” and is widely used to inform and target bat

conservation effort. It also forms on of

the UK Government’s biodiversity indicators.

One NBMP survey method which requires especial skill and

experience is hibernaculum counts. These must be carried out by bat-workers who

are specifically licensed for hibernaculum work, usually assisted by small

teams of dedicated volunteers. This is not easy work. Underground hibernacula

are often muddy, wet and physically demanding to access and to move around in. Safety

equipment is paramount and surveyors need to be suitably trained and equipped

to cope with conditions underground. Underground hibernacula may be natural

caves or man-made structures, such as tunnels, mine-workings etc. The latter

are usually disused and a continual assessment must be made as to whether a hibernaculum

is safe to survey. Bat conservation is important, but human health and safety

is always the priority.

Bats in Scottish underground hibernacula are usually found

on their own, or very occasionally in small groups. Often they are dispersed

throughout a large area and it is not unusual for a team of four surveyors to

spend several hours searching to find only a handful of bats. Depending on the

temperature and humidity conditions in a particular hibernaculum bats may be

found on roofs or walls but often they are concealed within cracks and

crevices, where they can find security from disturbance and a suitable

microclimate. It is rarely possible to fully census bats within a hibernaculum,

as many individuals may be invisible in deeper crevices or in areas unsafe to

survey or in some cases mine-workings are simply too large to survey

comprehensively. To ensure that data used by the NBMP is as robust as possible

a repeatable survey method is used: as far as possible each year’s surveys will

be done by the same number of people, with a similar mix of experience,

spending a similar amount of time on the survey and following the same route

through the hibernaculum. Although a long, hard survey may yield only a handful

of records of bats, when combined with dozens of other surveys around the

country and compared year-on-year useful population data starts to emerge.

Great effort is taken to ensure that disturbance of bats during

a hibernaculum survey is kept to an absolute minimum. Surveys are normally carried out twice each

winter, with several weeks gap. Noise is kept as low as possible and bats are

illuminated with torches only for as long as it takes to identify them. Bats

are never normally touched or handled and in more confined spaces care is taken

to avoid standing below hibernating bats or breathing on them, to avoid the

surveyor’s body temperature from having an impact.

A hibernating Natterer's Bat (Myotis nattereri)

Identifying bats within hibernacula is challenging and

requires a good deal of experience. Critical identification characteristics are

often invisible without handling a bat or hidden by the crevice the bat is in.

Surveyors are forced to use secondary identification characteristics such as

fur colour, face and ear shape, size of feet etc., all of which are difficult

to measure except on the basis of experience. Often it is only possible to

identify a bat to genus.

It isn’t usually possible to identify individual bats,

especially in hibernation when wings are tightly folded so that scars to the

wing membrane cannot be seen. It is possible to ring bats using loose,

horseshoe-shaped aluminium rings around the forearm, but this technique is used

more sparingly than for birds due to potential impacts on the bats, so it is

rare to see a ringed bat within a hibernaculum. In January 2010 I found a

Daubenton’s Bat hibernating in a tunnel high in the Lowther Hills. This bat not

only had a ring but also had most of one ear missing. “one-ear”, as she became

known had been rung by researchers working on behalf of Scottish Natural

Heritage, testing for rabies at Falls of Clyde nature reserve 35km away in

August 2009. Her injury seems not to

have prejudiced her ability to hunt successfully, as I have regularly recorded

her hibernating in the same place in the five years since then.

"One-ear" in hibernation. Her missing right ear and the ring on her forearm are clearly visible, as is condensation on her pelage.

It cannot be stressed highly enough how important

hibernacula are for bats in Scotland. The need for sites with stable, low

temperature and high humidity, combined with long-term security and lack of

disturbance means that suitable sites are not common and it is common for bats

to travel long distances to reach them. Finding and monitoring these sites is

essential if we are to protect them and to measure variation in bat populations.

Destruction of hibernacula is just one of many threats faced by our bats and

protecting their ability to hibernate safely is critical for the long-term

survival of these sensitive, vulnerable and oft-maligned animals.

Keep up to date with the latest posts Facebook.com/Davidsbatblog

.jpeg)